Of the Lord Who Measures Justly, Yet Mends by Grace

Prelude: When Pain Awakens the Question In the throes of aching sorrow,…

In a moment of intellectual twilight, when the threads of dawn blur into the shadows of darkness, man stands bewildered before the great mirror of the cosmos, asking it: “Am I the measure of all things, or is there a measure above me?” The mind, which has long sung the anthem of sovereignty and raised the banner of rebellion against every authority that cannot be measured, finds itself —before revelation— like a child before an ocean, unable to fathom where its shores might lie. At this profound juncture, where the paths of philosophy and religion intersect, the questions arise anew: Is the Sharia to be judged by reason, or is reason itself to be defined in the light of Sharia? And what are the limits of reason in the first place—and what grants it the right to pass judgement on that which was not shaped in its image?

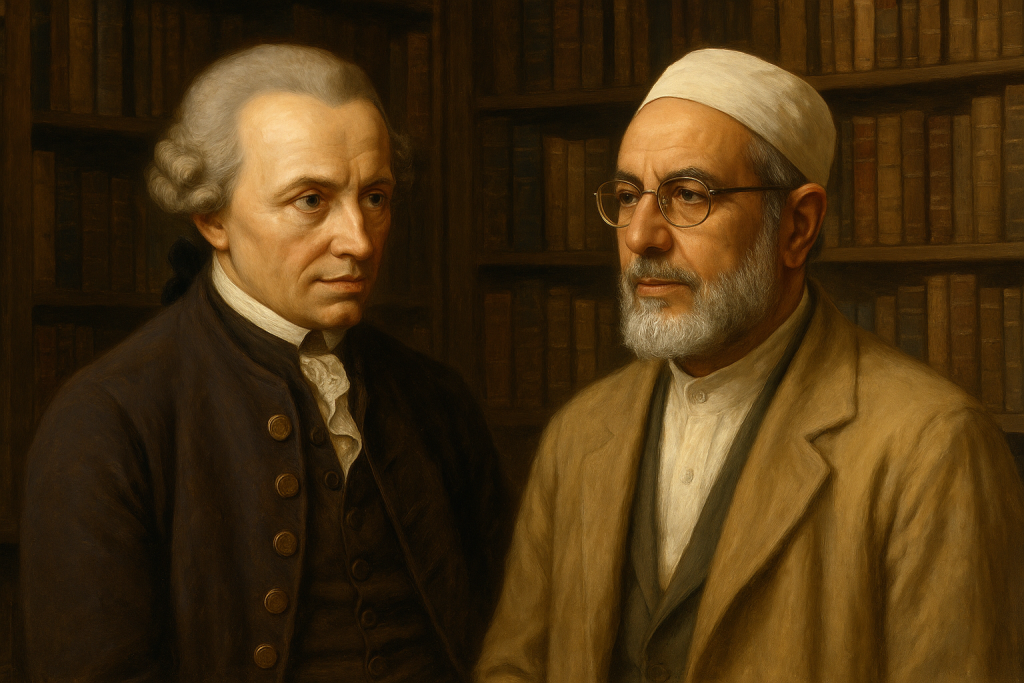

When Kant stood — his blue eyes open wide, his inner vision torn between faith and critique — to declare that reason is not absolute, contrary to what the Enlightenment philosophers had proclaimed, it was as though he were tolling a bell across the sky of thought: “Halt! Here ends the power of reason to know.” In his seminal work, Critique of Pure Reason, he did not attack religion; rather, he took aim at reason when it trespasses upon the realms of the unseen. He sought to say: there is a form of knowledge that arises neither from experience nor from analysis, but from something loftier — something beyond the reach of our usual epistemic tools. With severe philosophical precision, he traced the boundaries of human reason — boundaries that forbid it from leaping beyond appearances into what he called the thing-in-itself (das Ding an sich).

For instance, Kant drew a strict distinction between “the world as it appears to us” (phenomena) and “the world as it is in itself” (noumena). When we speak of God, the soul, or immortality, we possess neither sensory experience to prove them nor pure concepts of reason to generate them. These are, as he termed them, regulative ideas — they serve to orient our moral conduct and organise the operations of reason, but they do not constitute knowledge in the traditional sense. When a person says, for example, “There is a just God who will hold the oppressors to account,” they do not mean they have a mathematical proof of it, but that the idea morally compels them and gives existential direction. This is how the realm beyond the bounds of reason is formed — not as a denial of what lies beyond, but as an admission of the insufficiency of our tools before it.

Here, in this shadowed realm which Western philosophers dared to enter only as wanderers, Islamic discourse may step forth to proclaim its presence. The Sharia is not a human attempt to comprehend life; it is a manifestation of meaning from on high. It is not a linguistic text to be read like literature, but a light — one that can only be read from the posture of prostration, not defiance. And between prostration and defiance lies the fate of reason: either as an instrument of illumination, or as a shackle of disbelief.

Taha Abdurrahman —the thinker who wrote in ink and tears— did not merely stop at Kant’s gates; he scaled them and entered. From The Critique of Pure Reason, he seized its solid core: that reason is limited, that it does not hold the keys to all things, and that the unseen is not an epistemic field for reason, but a domain for spiritual connection. Yet Taha did not stop there; he went further: reason is not truly reason unless it is bound to ethics and submits to revelation — not as a diminishment of itself, but as the fulfilment of its own truth. Thus emerged what he called the “supported reason” (al-‘aqlul-mu’ayyad) as opposed to the “bare reason” (al-‘aqlul-mujarrad): a reason that sees in Sharia not a rival, but a guide.

A luminous example of this appears in Taha’s Rūḥud-Dīn, where he distinguishes between knowledge produced by bare reason and knowledge unveiled within the context of spiritual purification (Tazkiyah). The knower of God, in his view, does not merely rely on proof; rather, he internalises it, is refined through it, until it becomes direct awareness. This approach is evident in how he treats major philosophical concepts — such as freedom, which he does not define as mere liberation from constraint, but as a spiritual capacity to break free from the tyranny of desire and to submit to divine wisdom. Thus, the scales are reversed: reason no longer stands as the final judge, but as one illumined by a revelation that transcends it.

But the paradox that shallow thought fails to grasp is that many who call for “liberating reason” from the authority of the scripture, are in fact subjecting it to other authorities: such as modernity, the West, historicism, and psychological interpretation. They flee from the power of the unseen to the tyranny of shifting concepts. They declare a revolution against transmission (Naql), only to build their temples upon the altar of human interpretation. They believe they have freed reason, yet in reality, they have shackled it with constraints that have no reference other than mere whims.

From this, we understand how what appears to be a conflict between reason and revelation is, at its core, a struggle between two types of intellects: one that seeks truth with humility, and one that seeks dominance with arrogance and insolence. The Sharia does not reject reason, but it rejects its deification. One of the greatest signs of impending ruin is when we judge a divine discourse with a reason that has yet to understand itself, let alone explore the depths of its own limitations!

If we reflect on the state of Islamic thought today, we find that many attempts to “modernise the Sharia” are rooted in Western rationalism, without questioning it! The Sharia is sought to be made democratic, feminist, historical and humanistic… for no reason other than that Western reason has decided these are the highest values! It is as though we are re-establishing Islam according to an imported philosophical whim. Here, Kantian critique comes into play — not to submit to it, but to employ it: Western reason itself has acknowledged its limitations, so how can we take it as the standard by which to judge the revelation of the heavens?

What the Kantian philosophy offers, with its strict delineation of the domain of knowledge, opens the door to the establishment of an Islamic theory of knowledge that acknowledges and reveres reason, yet does not grant it the authority to issue final judgments. In the Islamic perspective, revelation is not merely an “epistemic given”, but rather light, guidance, clarification, and healing. Reason, in this view, is not an absolute authority, but a servant commanded — if it submits, it is illuminated; if it grows arrogant, it becomes engulfed in darkness.

Thus, when we draw inspiration from Kant’s boundaries of reason, and from Taha Abdurrahman’s horizon of the soul, we do not seek to craft a new understanding of Sharia, but rather to cement its place in the epistemological structure in a way that awakens the intellect from its oblivion to its status. We are not reinterpreting the scripture, but rather requalifying our tools to understand it; not with the logic of doubt or the understanding conditioned by familiar reason, but with the logic of spiritual purification and receptivity. The scripture is not a field for intellectual manoeuvring, but a domain for guidance; we read it not to judge it, but to refine ourselves through it.

The issue is not a conflict between the old clinging to tradition and the new yearning for renewal, nor between religion and thought as some like to portray it. It is much deeper than that: it is an existential crossroads between a reason that bowed to the call of prostration as its Lord commanded, and so it prostrated, and a reason that refused, grew arrogant, and said: “I am better than him” (Quran, 38:76). He who does not prostrate to the truth, prostrates to his arrogance, and he who does not support his intellect with the light of revelation, worships his desires.

It is the decisive choice between a reason that illuminates the path like a guiding star and a reason that wanders lost in the labyrinth of its own reflections.

Join the Discussion